What Animals Lived At The Arctic National Widlife Refuge

| Arctic National Wildlife Refuge | |

|---|---|

| IUCN category Four (habitat/species management area) | |

Refuge during summertime | |

Location in northern Alaska | |

| Location | North Gradient Borough and Yukon-Koyukuk Census Area, Alaska, United States |

| Nearest city | Utqiaġvik, Alaska pop. iii,982 Kaktovik, Alaska pop. 258 |

| Coordinates | 68°45′North 143°thirty′W / 68.750°N 143.500°W / 68.750; -143.500 Coordinates: 68°45′N 143°30′West / 68.750°North 143.500°W / 68.750; -143.500 |

| Expanse | 19,286,722 acres (78,050.59 km2) |

| Established | 1960 |

| Governing body | U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service |

| Website | Arctic National NWR |

The Chill National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR or Arctic Refuge) is a national wildlife refuge in northeastern Alaska, United states on Gwich'in country. Information technology consists of xix,286,722 acres (78,050.59 km2) in the Alaska N Slope region.[ane] It is the largest national wild animals refuge in the country, slightly larger than the Yukon Delta National Wildlife Refuge. The refuge is administered from offices in Fairbanks. ANWR includes a large variety of species of plants and animals, such as polar bears, grizzly bears, black bears, moose, caribou, wolves, eagles, lynx, wolverine, marten, beaver and migratory birds, which rely on the refuge.

Just beyond the border in Yukon, Canada, are two Canadian National Parks, Ivvavik and Vuntut.

History [edit]

The Arctic Refuge is part of the traditional homelands of many bands or tribes of the Gwichʼin people. For thousands of years, the Gwich'in accept chosen the coastal plain of the Arctic Refuge "Iizhik Gwats'an Gwandaii Goodlit" (The Sacred Identify Where Life Begins).[two]

The National Wildlife Refuge System was founded by President Theodore Roosevelt in 1903,[3] to protect immense areas of wildlife and wetlands in the United States. This refuge organisation created the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 which conserves the wildlife of Alaska.

In 1929, a 28-twelvemonth-old forester named Bob Marshall visited the upper Koyukuk River and the primal Brooks Range on his summer holiday "in what seemed on the map to be the near unknown section of Alaska."[iv]

In February 1930, Marshall published an essay, "The Problem of the Wilderness", a spirited defence of wilderness preservation in The Scientific Monthly, arguing that wilderness was worth saving not simply considering of its unique aesthetic qualities, simply because it could provide visitors with a take a chance for adventure.[5] Marshall stated: "There is just one hope of repulsing the tyrannical ambition of culture to conquer every niche on the whole globe. That hope is the organization of spirited people who will fight for the freedom of the wilderness."[six] The article became a much-quoted phone call to action and by the late 20th century was considered seminal past wilderness historians.[seven] According to environmental journalist Brooke Jarvis, "Marshall saw the enormous, largely unsettled Arctic lands he had explored as a possible antitoxin to this—not another risk to proceed chasing America'southward so-chosen Manifest Destiny but a gamble to finally stop chasing information technology." Fifty-fifty for Americans who would never travel in that location, "he thought they would do good knowing that it all the same existed in the condition it always had." "In Alaska alone," Marshall wrote, "tin can the emotional values of the borderland be preserved."[4]

In 1953, an article was published in the journal of the Sierra Gild by then National Park Service planner George Collins and biologist Lowell Sumner titled "Northeast Alaska: The Last Great Wilderness".[8] Collins and Sumner then recruited Wilderness Club President Olaus Murie and his wife Margaret Murie with an effort to permanently protect the area.

In 1954, the National Park Service recommended that the untouched areas in the Northeastern region of Alaska be preserved for inquiry and protection of nature.[9] The question of whether to drill for oil in the National Wildlife Arctic Refuge has been a political controversy since 1977. The debate mainly concerns section 1002 in the ANWR. Section 1002 is located on the coastal plainly where many of the Arctic'southward diverse wildlife species reside. The usage of section 1002 in ANWR depends on the amount of oil worldwide.[10] There are two sides of this debate: support for drilling and the opposition of drilling. Most of the supporters for drilling are large oil companies and political campaigners who sought to get afterwards the resources that could be found in the refuge. The oppositions of drilling include people who currently reside in Alaska and people who want to preserve the wild fauna and land for time to come considerations.

In 1956, Olaus and Mardy Murie led an expedition to the Brooks Range in northeast Alaska, where they defended an unabridged summer to studying the land and wild animals ecosystems of the Upper Sheenjek Valley.[11] The determination resulting from these studies was an ever-deeper sense of the importance of preserving the surface area intact, a decision that would play an instrumental office in the decision to designate the expanse as wilderness in 1960. Every bit Olaus would afterwards say in a 1963 speech to a meeting of the Wild animals Management Association of New Mexico State University, "On our trips to the Arctic Wildlife Range nosotros saw clearly that it was not a place for mass recreation... Information technology takes a lot of territory to keep this alive, a living wilderness, for scientific observation and for esthetic inspiration. The Far Due north is a frail place."[12] Environmentalist Celia M. Hunter met the Muries and joined the fight. Founding the Alaska Conservation Society in 1960, Celia worked tirelessly to garner back up for the protection of Alaskan wilderness ecosystems.[13]

The region first became a federal protected area in 1960 by order of Fred Andrew Seaton, Secretary of the Interior under U.Due south. President Dwight D. Eisenhower. In 1980, Congress passed the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act. The bill was signed into police force by President Jimmy Carter on ii Dec 1980.[14]

Eight million acres (32,000 km2) of the refuge are designated as wilderness expanse, the Mollie Beattie Wilderness.[15] The expansion of the refuge in 1980 designated 1.five million acres (6,100 km2) of the coastal plain equally the 1002 surface area and mandated studies of the natural resources of this area, especially petroleum. Congressional authorization is required before oil drilling may go along in this area. The remaining 10.1 one thousand thousand acres (41,000 km2) of the refuge are designated as "minimal management," a category intended to maintain existing natural conditions and resource values. These areas are suitable for wilderness designation, although in that location are presently no proposals to designate them as wilderness.

Currently, there are no roads within or leading into the refuge, but there are a few Native settlements scattered within. On the northern border of the refuge is the Inupiat hamlet of Kaktovik (population 258)[16] and on the southern purlieus the Gwich'in settlement of Chill Village (population 152).[16] A pop wilderness road and historic passage exists between the 2 villages, traversing the refuge and all its ecosystems from boreal, interior forest to Arctic Ocean coast. Generally, visitors gain access to the land by aircraft, simply information technology is also possible to reach the refuge by gunkhole or past walking (the Dalton Highway passes nigh the western edge of the refuge). In the United States, the geographic location most remote from human trails, roads, or settlements is found here, at the headwaters of the Sheenjek River.

Geography [edit]

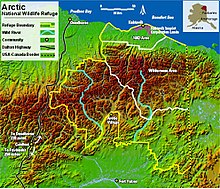

Natural-color satellite image of the refuge. Thick white lines delineate refuge boundaries, and thin white lines separate areas within the park.

Chill National Wildlife Refuge Map.

The Chill is mostly an ocean surrounded past land. The Arctic is relatively covered by h2o, much of it is frozen. The glaciers and icebergs in the Chill make upward about 10% of Earth's country area. Most of the Chill'southward liquid saltwater is from the Arctic Ocean'due south basin. Some parts of the body of water's surface are frozen all or well-nigh of the year. The Chill area is mainly known for sea ice surrounding the region. The Arctic experiences extreme solar radiations. During the Northern Hemisphere's winter months, the Arctic experiences cold and darkness which makes information technology one of the unique places on Earth. North America's ii largest tall lakes (Peters and Schrader) are located inside the refuge. ANWR is nearly the size of South Carolina.

Area 1002 of the Arctic National Wild animals Refuge coastal plain, looking due south toward the Brooks Range mountains.

The refuge supports a greater variety of establish and animal life than any other protected surface area in the Chill Circle. A continuum of six dissimilar ecozones spans almost 200 miles (300 km) north to s.

Along the northern coast of the refuge, the barrier islands, coastal lagoons, common salt marshes, and river deltas of the Chill littoral tundra provide habitat for migratory waterbirds including ocean ducks, geese, swans, and shorebirds. Fish such as dolly varden and Chill cisco are institute in nearshore waters. Coastal lands and sea ice are used by caribou seeking relief from biting insects during summertime, and by polar bears hunting seals and giving birth in snowfall dens during wintertime.

The Arctic littoral plain stretches s from the coast to the foothills of the Brooks Range. This area of rolling hills, modest lakes, and n-flowing, braided rivers is dominated by tundra vegetation consisting of low shrubs, sedges, and mosses. Caribou travel to the littoral plain during June and July to requite nascence and heighten their young. Migratory birds and insects flourish hither during the cursory Arctic summer. Tens of thousands of snowfall geese stop hither during September to feed before migrating southward, and muskoxen live here yr-round.

South of the coastal evidently, the mountains of the eastern Brooks Range rise to nearly 9,000 anxiety (ii,700 k). This northernmost extension of the Rocky Mountains marks the continental separate, with due north-flowing rivers emptying into the Arctic Ocean and due south-flowing rivers joining the great Yukon River. The rugged mountains of the Brooks Range are incised by deep river valleys creating a range of elevations and aspects that support a diverseness of low tundra vegetation, dense shrubs, rare groves of poplar trees on the north side and spruce on the southward. During summer, peregrine falcons, gyrfalcons, and gilded eagles build nests on cliffs. Harlequin ducks and red-breasted mergansers are seen on swift-flowing rivers. Dall sheep, muskoxen, and Alaskan Chill tundra wolves are active all twelvemonth, while grizzly bears and Arctic ground squirrels are frequently seen during summer simply hibernate in winter.

The southern portion of the Arctic Refuge is within the Interior Alaska-Yukon lowland taiga (boreal forest) ecoregion. Beginning as predominantly treeless tundra with scattered islands of black and white bandbox trees, the forest becomes progressively denser equally the foothills yield to the expansive flats north of the Yukon River. Frequent woods fires ignited by lightning event in a complex mosaic of birch, aspen, and bandbox forests of various ages. Wetlands and southward-flowing rivers create openings in the forest awning. Neotropical migratory birds brood hither in leap and summer, attracted by plentiful food and the variety of habitats. Caribou travel here from farther due north to spend the winter. Other year-round residents of the boreal forest include moose, polar foxes, beavers, Canadian lynxes, martens, reddish foxes, river otters, porcupines, muskrats, black bears, wolverines, and minks.

Each year, thousands of waterfowl and other birds nest and reproduce in areas surrounding Prudhoe Bay and Kuparuk fields and a healthy and increasing caribou herd migrates through these areas to calve and seek respite from annoying pests.

Drilling [edit]

| External video | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

The question of whether to drill for oil in the ANWR has been an ongoing political controversy in the United States since 1977.[xviii]

The controversy surrounds drilling for oil in a subsection of the coastal plain, known every bit the "1002 expanse".[nineteen] ANWR is xix,286,722 acres (78,050.59 km2). The littoral plain is ane,500,000 acres (6,100 kmii). The electric current proposal would limit development to two,000 acres (8.i km2) of that plain.[xx]

Much of the contend over whether to drill in the 1002 area of ANWR rests on the amount of economically recoverable oil, as it relates to earth oil markets, weighed confronting the potential impairment oil exploration might have upon the natural wildlife, in particular the calving footing of the Porcupine caribou.[21] The Chill was plant to take an immense amount of oil and natural gas deposits. Specifically, ANWR occupies state beneath which in that location may be vii.vii to eleven.8 billion bbl (1.22 to 1.88 billion m3) of oil. In Alaska, it is known for major oil companies to work with the indigenous groups, Alaska native corporations, to drill and consign millions of barrels of oil each yr.

Nearly all countries in the Arctic are rushing to merits the resource and minerals found in the Arctic. This rivalry is known as the "New Cold State of war" or "Race for the Arctic". Republicans argued for years that drilling should be allowed since there would be over $xxx million of revenue and create every bit many as 130,000 jobs. Furthermore, Republicans claim that drilling volition make the The states more independent from other countries because it volition increase the oil reserves of the land. For Republicans to enable exploitation of the oil, they would need 51 votes in the Senate to pass the House bill that cannot include the ANWR drilling linguistic communication.[ citation needed ]

People who oppose the drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge believe that it would be a threat to the lives of ethnic tribes. Those tribes rely on the ANWR'south wildlife, the animals and plants that reside in the refuge. Moreover, the exercise of drilling could present a potential threat to the region as a whole. When companies are exploring and drilling they are extracting the vegetation and destroying permafrost which can cause harm to the country.

In Dec 2017, Congress passed the Trump administration'southward tax bill which included a provision introduced by Senator Lisa Murkowski that required Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke to approve at least 2 lease sales for drilling in the refuge.[22] [23] In September 2019, the administration said they would like to see the unabridged coastal obviously opened for gas and oil exploration, the most aggressive of the suggested development options. The Interior Section's Bureau of Country Management (BLM) has filed a concluding environmental touch on statement and plans to outset granting leases by the end of the year. In a review of the statement the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service said the BLM'southward last argument underestimated the climate impacts of the oil leases because they viewed global warming as cyclical rather than human-made. The assistants'south program calls for "the construction of as many as four places for airstrips and well pads, 175 miles [282 km] of roads, vertical supports for pipelines, a seawater-treatment plant and a clomp landing and storage site."[24] [25]

In response to public outcry and concerns of worsening climate change, U.S. banks Goldman Sachs, JPMorgan Chase and Wells Fargo publicly appear that they will not fund oil and gas projects in the Arctic region.[26] These decisions come as President Donald Trump'south administration is proceeding with planned lease sales in the Refuge.

On August 17, 2020, Interior Secretary David Bernhardt announced an oil and gas leasing plan in the Chill National Wild fauna Refuge.[27] This will allow for future drilling in the Refuge.

An auction for the land leases was held on Jan 6, 2021. Of the 20-two tracts upwardly for sale, full bids were offered for merely xi tracts. An Alaskan state entity, the Alaska Industrial Development and Export Authority, won the bids on nine tracts. Two pocket-size independent companies, Knik Arm Services LLC and Regenerate Alaska Inc, won one tract each. The sale generated $14.four 1000000, significantly lower than the $1.8 billion guess from the Congressional Budget Office in 2019, and the auction did non receive bids from any oil and gas companies.[28]

On January xx, 2021, newly inaugurated President Joe Biden issued an executive social club to temporarily halt drilling activity in the refuge.[29]

On June 1, 2021, President Biden suspended all of the oil drilling leases issued by the previous administration, pending a review of the environmental impacts and legal ground of the leases.[30] [31]

Climate change [edit]

Scientists are noticing that sea levels are ascent at increasing rates. Sea levels are rise considering polar ice caps are melting at a rapid step. This process starts in the Arctic region, specifically in Alaska. Researchers at Oxford University explained that increasing temperatures, melting glaciers, thawing permafrost, and rising body of water levels are all indications of warming throughout the Arctic.[32] Bounding main Ice has thinned and decreased. Thinning has occurred due to the sun melting the water ice at a college pace. This backs up the concept of how the Arctic region is the beginning to be affected by climatic change. Shorefast ice tends to course subsequently in autumn. In September 2007, the concentration of body of water ice in the Arctic Sea was significantly less than ever previously recorded. Although the total area of water ice built upwards in contempo years, the corporeality of ice continued to turn down because of this thinning.[33] Climate change is happening faster and more severe in the Chill compared to the residuum of the world. According to NASA, the Arctic is the outset identify that volition exist affected past global climate change.[34] This is because shiny ice and snowfall reflect a high proportion of the sun'south free energy into space. The Arctic gradually loses snow and ice, blank rock and water absorb more than and more of the dominicus's free energy, making the Arctic fifty-fifty warmer. This phenomenon is called the albedo effect.[35]

Porcupine caribou herd [edit]

This area for possible hereafter oil drilling on the coastal plains of the Chill National Wildlife Refuge, encompasses much of the Porcupine caribou calving grounds. Migratory caribou herds are named after their birthing grounds, in this case the Porcupine River, which runs through a large role of the range of the Porcupine herd.[36] [37] In 2001, some biologists feared development in the Refuge would "push caribou into the foothills, where calves would be more prone to predation."[21] Though numbers fluctuate, at that place were approximately 169,000 animals in the herd in 2010.[36] [37] Their annual land migration of 1,500 miles (2,400 km), betwixt their winter range in the boreal forests of Alaska and northwest Canada over the mountains to the littoral plain and their calving grounds on the Beaufort Sea littoral patently,[38] is the longest of whatsoever land mammal on earth.

In 2001, proponents of the development of the oil fields at Prudhoe Bay and Kuparuk, which would exist approximately lx miles (97 km) west of the Refuge, argued that Central Arctic caribou herd, had increased its numbers "in spite of several hundred miles of gravel roads and more than a grand miles of elevated piping." Nonetheless, the Central Arctic herd is much smaller than the Porcupine herd, and has an surface area that is much larger.[21] By 2008 the Cardinal Arctic caribou herd had approximately 67,000 animals.[37]

Polar bears [edit]

The Arctic National Wildlife Refuge is straight connected to Polar Bears. These bears are known for traveling in the region to den and give nativity. Nearly 50 of these species migrate forth the declension to the refuge in September. These bears extend more than than 800 miles (1,300 km) along the declension of Northern Alaska and Canada. Due to changes in climate, Polar bears are recorded to now spend more time on state waiting on new sea ice to form, as they depend on sea water ice for much of their hunting. This limits their power to hunt seals to build up fatty for hibernation. Much controversial, the polar bears are widely afflicted by the climate change happening in this region. Pregnant females are forced to move onshore at unusual times to dig their dens. Commonly, the bears are known to dig their dens in November, then requite nascence to one to two tiny cubs in December or January. The mothers then nurse and care for the young until March or early April, when they loom from the dens. Subsequently several days adapting to the outside environment, the families get out the dens. They move back to the bounding main ice to hunt ringed seals and other prey. The cubs always stay with their mothers for virtually the adjacent two and a half years.[39] Polar Bears follow the trace of current conveying sea ice which leads them to travel south. This often leads them to relying on trash abundances for nutrition. This food source impacts the health of polar bears negatively. They as well brainstorm targeting unusual animals every bit prey.[forty] [41]

The Chill National Wildlife Refuge is the only refuge that regularly dens polar bears in that local region, and contains the most consequent number of polar bears in the area.[ citation needed ]

Marine ecosystem [edit]

The Arctic basin is the shallowest bounding main basin on Earth. It is the least salty, because of low evaporation and large current of freshwater from rivers and glaciers. River mouths and calving glaciers, are continually moving ocean currents contribute to a unique marine ecosystem in the Arctic. The cold, circulating water is rich in minerals, too as the microscopic organisms (such as phytoplankton and algae) that need them to grow. Marine animals thrive in the Chill. In that location are 12 species of marine mammals of the Arctic found in the refuge. They consist of 4 species of whales, polar bears, the walrus and six species of ice-associated seals, sperm whales, bluish whales, fin whales, humpback whales, killer whales, Harbor Porpoise. The Chill marine food web consists of Main consumers, Secondary consumers, 3rd consumers, and scavengers. Marine mammals in the Arctic are experiencing astringent impacts, including effects on migration, from disturbances such as noises from industrial action, offshore seismic oil exploration, and well drilling.

People of the Arctic National Wild fauna Refuge [edit]

The people who live in this Refuge have become accustomed over thousands of years to both survive and prosper in these harsh conditions. Different cultures may exist found in the various regions of the Arctic, from the Sámi in Finland and Norway to the Chuckchi and Koyaki in Siberia. In that location are two villages whose history are tied to the Chill Refuge and accept been for thousands of years which are the Kaktovik and the Arctic Village.[42] Kaktovik is an Inupiaq village of about 250 current residents located inside the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge along the Beaufort Sea. The Inupiaq Village is used as a traditional summer fishing and hunting location. Furthermore, this location also became a usual place for commercial whalers in the late 1800s, which led them to go permanent residents in the Refuge.

See likewise [edit]

- Alaska Wilderness League

- Arctic Refuge drilling controversy

- Jonathon Solomon

- National Petroleum Reserve–Alaska

- Natural resources of the Chill

- Arctic policy of the United States

- The Last Alaskans (idiot box series)

References [edit]

- ^ "USFWS Annual Lands Study, 30 September 2009" (PDF).

- ^ "The Coastal Manifestly – The Sacred Place Where Life Begins". Gwich'in Steering Commission . Retrieved eleven November 2021.

- ^ Shush, Leann. "Multifariousness of species calls wildlife refuge home". U.South Fish & Wildlife Service. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ^ a b "The Terminal Stand up of the Concluding Great Wilderness". Sierra Club. 29 Oct 2018. Retrieved 30 November 2018.

- ^ Shabecoff, P. (2012). A Tearing Green Fire: The American Environmental Movement. Island Press. ISBN978-one-59726-759-5 . Retrieved 30 November 2018.

- ^ Nash, R.F.; Miller, C. (2014). Wilderness and the American Mind: Fifth Edition. Yale University Printing. p. 200. ISBN978-0-300-15350-vii . Retrieved 30 November 2018.

- ^ Glover, p. 116

- ^ Kaye, Roger. "The Arctic National Wildlife Refuge: An Exploration of the Meanings Embodied in America's Concluding Great Wilderness" (PDF). Book 2. No. xv. USDA Forest Service Proceedings. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 December 2013. Retrieved sixteen July 2014.

- ^ "Time Line: Establishment and management of Arctic Refuge - Arctic". U.Southward. Fish and Wild animals Service . Retrieved 30 November 2018.

- ^ "Regional Studies - Alaska Petroleum Studies, Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR-1002 area)". energy.usgs.gov . Retrieved 25 Apr 2018.

- ^ Krear, PhD, Robert (July 2000). "The Muries Made the Difference". The Muries Voices for Wilderness & Wildlife: 19–twenty.

- ^ Murie, Olaus. "Look Ye As well While Life Lasts". The Muries: Voices for Wilderness and Wildlife.

- ^ alaskaconservation.org

- ^ King, Seth S. (3 December 1980). "Carter Signs a Bill to Protect 104 Million Acres in Alaska". New York Times. nytimes.com. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- ^ Wilderness Found, University of Montana (2011). "Mollie Beattie Wilderness". Wilderness.internet. Archived from the original on 16 Oct 2012. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ a b http://factfinder.census.gov/dwelling house/saff/main.html?_lang=en. Retrieved 13 September 2008. [ dead link ]

- ^ "President Obama Calls on Congress to Protect Arctic Refuge equally Wilderness". whitehouse.gov. 25 January 2015. Retrieved 26 Jan 2015 – via National Archives.

- ^ Shogren, Elizabeth. "For thirty Years, a Political Boxing Over Oil and ANWR." All Things Considered. NPR. 10 Nov 2005.

- ^ "Potential Oil Production from the Coastal Plain of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge: Updated Cess". U.s.a. DOE. Archived from the original on three Apr 2009. Retrieved 14 March 2009.

- ^ Congress moves to 'drill, baby, drill' in Alaska's ANWR. Here'southward what y'all should know

"Surface evolution on the federal country would exist limited to 2,000 acres." - ^ a b c Mitchell, John. "Oil Field or Sanctuary?" National Geographic 1 August 2001.

- ^ D'Angelo, Chris (February 2018). "Trump Says He 'Really Didn't Care' About Drilling Arctic Refuge. And then A Friend Chosen". HuffPost . Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Automobile: Trump begins to speak at minute 1:forty. "ANWR wild fauna refuge". YouTube . Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- ^ "Trump assistants opens huge reserve in Alaska to drilling". The Washington Post . Retrieved xx October 2019.

- ^ Holden, Emily (12 September 2019). "Trump opens protected Alaskan Arctic refuge to oil drillers". The Guardian . Retrieved 22 October 2019.

- ^ "Wall Street backs away from Arctic drilling amid Alaska political heat". Reuters. 3 March 2020. Retrieved 4 March 2020.

- ^ Gregory Wallace and Chandelis Duster. "Trump administration announces plans to drill in Arctic National Wild fauna Refuge". CNN . Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- ^ Nichola Groom; Yereth Rosen (half dozen January 2021). "Oil drillers shrug off Trump's U.Southward. Arctic wild fauna refuge auction". www.reuters.com . Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- ^ "Biden plans temporary halt of oil activity in Arctic refuge". AP NEWS. 20 Jan 2021.

- ^ Davenport, Coral; Fountain, Henry; Friedman, Lisa (1 June 2021). "Biden Suspends Drilling Leases in Arctic National Wild animals Refuge". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved i June 2021.

- ^ "Biden Administration to Append Trump-Era Oil Leases in Arctic Refuge". June 2021.

- ^ "Climatic change in the Arctic | National Snow and Ice Data Eye". nsidc.org . Retrieved 25 Apr 2018.

- ^ "Quick Facts on Arctic Ocean Ice | National Snowfall and Ice Data Heart". nsidc.org . Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- ^ Jackson, Randal. "Global Climate Modify: Effects". Climate change: Vital Signs of the Planet . Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- ^ "Albedo effect". Norwegian Polar Institute . Retrieved 25 Apr 2018.

- ^ a b Campbell, Cora (2 March 2011), Porcupine Caribou Herd shows growth, Press release, Juneau, Alaska: Alaska Department of Fish and Game

- ^ a b c Kolpashikov, Fifty.; Makhailov, V.; Russell, D., "The role of harvest, predators and socio-political environment in the dynamics of the Taimyr wild reindeer herd with some lessons for N America", Ecology and Society

- ^ Mitchell, John (1 August 2001), Oil Field or Sanctuary?, National Geographic, retrieved fifteen Jan 2014

- ^ Service, U.S. Fish and Wildlife. "U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service". world wide web.fws.gov . Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- ^ "Arctic Refuge Has Lots of Wildlife—Oil, Possibly Not So Much". 19 December 2017. Retrieved 25 Apr 2018.

- ^ "Threats to Polar Bears". Retrieved 25 Apr 2018.

- ^ "Arctic National Wild fauna Refuge". arcticcircle.uconn.edu. Archived from the original on 6 February 2012. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

External links [edit]

- Official ANWR website

- Congressional Research Service (CRS) Reports regarding the Arctic National Wild animals Refuge

- An article about the land and the people of Arctic Wildlife Refuge

- Text of Wilderness Act of 1964

- U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service website about the Refuge

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arctic_National_Wildlife_Refuge

Posted by: blanksenone1940.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Animals Lived At The Arctic National Widlife Refuge"

Post a Comment